The fundamental nature of news and news reporting is that the bad news gets all the attention. Tragedies, conflicts and crises get reported; success stories rarely do. But the end result is that a non-Native audience may well come to the conclusion that Aboriginal people are a troubled, plagued and contentious people.

– Media Awareness.ca

It’s a common tale, amongst Indigenous people who grew up watching Western movies: when it came time to play ‘Cowboys and Indians,’ Indigenous kids often opted for the role of cowboy. Who would want to play the Indian — that violent and inept tomahawk-wielding savage whose appearances were marked by ominous drum themes?

Credit: Union of BC Indian Chiefs

News stories from Indian Country, so often negative in tone and subject matter, aren’t unlike that evil Hollywood Indian. Who would blame Indigenous Peoples for being weary of “disaster coverage” from their communities? What impact does a relentless stream of negative news have on the self-esteem of Indigenous youth? If non-Indigenous audiences form their impressions about Indigenous Peoples from the news, who would be surprised if they develop unfavourable opinions?

That said, it’s hard to fight the prevailing wisdom of most newsrooms: bad news is sexy. Years of experience have taught us that news about conflict, disaster, and death grabs eyeballs and sells papers.

But, if we don’t attempt to strike a balance in our coverage — between the positive and negative — we risk alienating our Indigenous audience, and over time, contributing to an unbalanced perspective of Indigenous communities.

Tell a range of stories. Hard news, human interest and features. If you have a track record of presenting a variety of Indigenous perspectives – solutions as well as problems, reconciliation as well as discord – Indigenous people will notice and you’ll discover that almost any subject is fair game.

Include Indigenous people in “non-Indigenous” stories. Don’t only seek out Indigenous people for “Indigenous” stories (whether those stories are “good” or “bad”). Consult Indigenous people for any sort of local, provincial, national and international story. What do Indigenous folks think about the weather, the war in Afghanistan, or interest rates? When searching for parents for your annual back-to-school story, can you interview a Wabegijig and a Littlechild, as well as a Smith and a Singh?

Credit: Government of Alberta

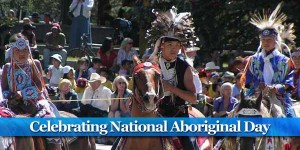

Avoid “calendar journalism.” Some newsrooms, in an attempt to portray minorities more equitably, roll out annual stories about multicultural celebrations, such as Chinese New Year or Diwali. The Indigenous versions of this “calendar journalism” are the annual story on pow-wows, cultural gatherings, and National Indigenous Peoples Day. These events are undoubtedly important to Indigenous Peoples, but studies of minority news audiences show they want more than fluffy stories about food and festival. They want up-to-date, accurate and factual coverage of events that reflect and impact their lives. In other words, they want journalism – so don’t pitch your journalistic principles out the window just to meet a diversity quota.

Credit: urbanrez.ca

Don’t bury the “good news.” Most newsrooms regularly shop for human-interest and “feel-good” stories, to balance out all that violence and tragedy our audience tell us they dislike. In fact, it’s not too hard to find “good news” or “success” stories involving Indigenous Peoples, but these stories often get buried — at the back end of newscasts or in the lifestyle sections of newspapers.

Don’t let “bad news” grab all the attention. Take credit for that strong human-interest story (and balance out your audience’s perception of Indigenous Peoples), by using promotional spots at your disposal – whether its an ad on your website, or targeted Tweets, or “bumpers” early on in a broadcast to promote stories that the audience might otherwise overlook.

Don’t shy away from “bad news.” In an effort to achieve balanced coverage of Indigenous communities, journalists shouldn’t pussyfoot around controversial issues, or neglect their role as watchdogs. It’s our job to ask accountability questions. Indigenous Peoples themselves want to know if there’s corruption or mismanagement within their own organizations, or if individuals are being mistreated within their community. “Negative” media attention can be a powerful catalyst for “positive” social change.