04 Apr On #TRC #86 & how to get more Indigenous reporters into newsrooms

In late 2015, Erin Sylvester of Ryerson Review of Journalism interviewed me for an article she was writing on the Indigenous Reporters Program from Journalists for Human Rights. The conversation was wide-ranging, as she was looking at the IRP as part of a larger trend to include more Indigenous reporters in Canadian newsrooms. Here’s a transcript of other stuff we talked about.

Erin: Do you think that there are more Indigenous people going in to journalism? Is the makeup of a newsroom changing?

McCue: It is changing, slowly but surely and that’s really encouraging to me compared to when I started in the newsroom over 15 years ago. That said, there are still some significant barriers. One of them is education levels amongst Aboriginal people are still lagging far behind the rest of Canadians, and that is shameful and needs to change and we’re not going to see more professional journalists from First Nations communities unless that broader issue of educational representation improves. So that’s one issue. The second issue is that there has been a historic distrust by many Aboriginal people of the mainstream media, because of the misrepresentation of Aboriginal people in the media. So young Aboriginal people may not necessarily see a home for themselves in mainstream newsrooms where it can be either A) a difficult work environment for them or B) they may not be able to pursue the kinds of stories that they want to pursue. The third issue is that there needs to be more cultural awareness training in mainstream newsrooms about diversity in your newsroom and what that means. I still don’t see enough newsrooms taking that seriously. And so if we want to encourage Aboriginal voices in our newsrooms, who are bringing us Aboriginal perspectives on our news outlets, then we need to understand that that means the newsroom need to be a culturally safe place for those Aboriginal reporters to operate.

Erin: How can we encourage more Indigenous people to work in journalism?

McCue: Like the movie Field of Dreams where it was said, ‘If you build it they will come,’ I think that’s what’s happening in the newsrooms. As you attract more Aboriginal staff to mainstream newsrooms, their voices and perspectives start to get incorporated into the daily decision making of the newsroom, and so that has a snowball effect. As you start to see more Aboriginal coverage, then you’ll start to attract more Aboriginal audiences and attract more young Aboriginal writers and storytellers to come and be part of your organization. The other thing which I really think has started to change is that – change hopefully for the better the amount of Aboriginal issues being covered – is that news audiences are fragmenting. Mainstream newsrooms are recognizing that they need to reach out to a broader section of the community if they’re going to survive. And we are very aware via social media that we have substantial Aboriginal audiences across the country that are being more vocal about the kinds of coverage that we offer on Aboriginal issues, and I think that’s helping. In short, I think Aboriginal audiences are holding mainstream newsrooms to account for their Aboriginal coverage and that’s helping, hopefully, improve and increase the amount of Aboriginal coverage. So Twitter, Facebook, whatever, we’re hearing from Aboriginal audiences that they want better, and that’s a good thing and that’s demanding and forcing mainstream newsrooms to provide better coverage.

Erin: What are examples of newsrooms or news organizations that are getting it right?

McCue: Well of course I’m biased, but two years ago, we launched CBC Aboriginal and our analytics show people are interested in hearing about the news in Aboriginal communities. So that is a great sign. And that CBC Aboriginal digital platform has grown and expanded into a one hour network radio show, Unreserved, and has continued to feed stories and feature into out mainstream CBC programs, like The National and The Current, on issues like missing and murdered Indigenous women and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Just in the past two years, that is a great example of coverage at CBC having improved. And of course, again, I’m completely and totally biased there. APTN, it’s fantastic to see how the newscast has matured and they are delivering award-winning news now that is setting the agenda in this country and I’m so happy to see that.

Erin: You’ve mentioned the Reporting in Indigenous Communities course you teach at UBC. What’s the goal of that class?

McCue: The goal, the simple goal of the class, is—most of my students are non-Aboriginal, we have very few Aboriginal students at the journalism school—so the goal of my class is to ensure A) that students have a base level of cultural competency when they go and report on First Nations issues and to adapt their journalism practice to take into account Aboriginal cultural protocols. The secondary goal is to deliver outstanding journalistic content on First Nations in B.C.’s Lower Mainland that reaches a wide mainstream audience. And so all of our stories that we produce in the class are delivered in the mainstream media, primarily CBC, but we’ve been in The Globe and Mail, the Vancouver Sun, and The Tyee.

Erin: Are journalism schools at fault for not teaching their students enough about First Nations issues?

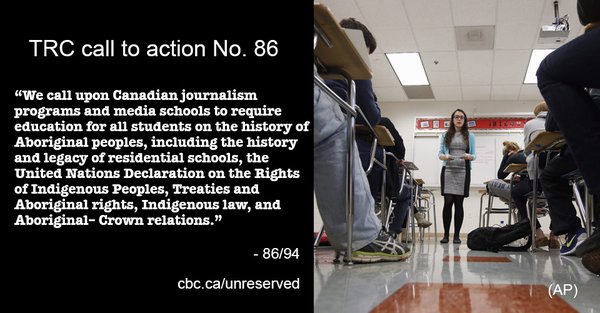

McCue: Of course they’re at fault. Of course they’re at fault! And one only needs to look at recommendation number 86 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to understand that.

There’s an important analytical body that has looked at this problem extensively and said, ‘We have an issue here: journalism schools.’ From my perspective, journalism schools across this country speak well about the need for diversity in their student body and their curriculum. However, I have yet to see the proper resourcing at other journalism schools in Canada, other than UBC, that makes comprehensive and extensive curricula about Indigenous issues come to fruition. The directors of the journalism schools in Canada need to stop paying lip service to diversity and Indigenous issues and start actually making this content a reality for journalism students in Canada, and if they don’t then we’re doing a disservice to our students who are going to, inevitably, be reporting on First Nations issues if they’re working in a Canadian newsroom.

Erin: How should journalism schools do a better job of teaching students about these communities?

McCue: It’s not rocket science. There need to be courses about Aboriginal issues taught in journalism schools. There are plenty of ways that that can be done. Having a brown bag lunch lecture or a one-off lecturer to come and talk about it, that’s wonderful, that’s great, and I know that there are schools across the country that are doing that. But if students are actually going to start to understand some of the complexities of working in Indigenous communities, and other diverse communities, then they need more than a brown bag lunch lecture.

Erin: Do you think that journalism schools will be able to fix the way that they teach and start addressing these holes in the curriculum?

McCue: Oh, of course I do. I live in hope. I think that there are lots of indications that the conversation between Aboriginal people and the rest of Canada is improving, that the bridges are being built, and that reconciliation is possible. And I think journalism needs to be a large part of that bridge building, and that will happen by educating journalists about some of the sins of our past and how we can improve things for the future.

Erin: Will including better education about First Nations in journalism schools attract more Indigenous students as well?

McCue: When I put on my First Nations educator hat, that’s a more challenging question about whether building Aboriginal programs necessarily attracts Aboriginal journalists. I know that certainly that’s what’s happened in many different fields. Education and law, for example, or social work, have found that when they start to develop First Nations specific programming, that attracts more First Nations students. I can’t say for sure whether or not that’s going to happen in journalism. It’s still too early to predict that, and just building a course doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to attract a boatload of First Nations students. There needs to be all kinds of other things, in terms of recruitment and support once they get to the school, and all kinds of other things which will guarantee educational success. But building the content is a good first step towards improving First Nations representation in journalism schools.

CBC Indigenous staff – hosts, reporters, producers, camera operators – from across Canada gather in Winnipeg in February 2016.

Erin: So we’ve talked about some challenged for Indigenous people looking to get into journalism. But you are a First Nations journalist.

McCue: I am, in fact, yes.

Erin: How did it work out for you?

McCue: What do you want to know?

Erin: How did you get where you are? How did you get started in journalism? What sort of challenges did you face?

McCue: How did I get where I am… I got where I am because I started writing for a student newspaper in my first year of undergrad and absolutely fell in love with journalism. So the work that I did at that student newspaper turned in to a job on a show called Road Movies, which had me travelling across the country and telling stories. And so all of that led to a career in journalism. I guess the biggest challenge that I felt that I faced, as a young Aboriginal reporter in the CBC Vancouver newsroom was trying to pitch stories with Aboriginal content. And that was frustrating and often discouraging. I’m not the first Aboriginal person to have experienced that in a newsroom and probably not the last either. You know, there are plenty of people who get discouraged or frustrated about the way that decisions get made about what makes the news every evening. That was the biggest challenge for me, was trying to impress upon the folks in my newsroom who were making those decisions that the kinds of stories that I was pitching were, quote, ‘newsworthy.’

Erin: Do you think that attitude is changing?

McCue; Yeah I think, I mean, it’s changed for me because I am, gosh, a veteran reporter now, so there is some recognition in the work that I do and an acknowledgement of the kinds of ideas that I bring to the table. I’m extremely lucky to work with CBC The National and to have them take seriously my perspective on Indigenous issues, and I feel like I’m heard, and so that’s great. Is it changing CBC-wide? Slowly but surely, yes, I think it is. But it’s still difficult for a young Aboriginal reporter to walk in through the doors and to try to bring their story ideas to fruition on our nightly newscasts. That’s still gong to be a challenge every young First Nations reporter is going to face when they come in to a newsroom. A mainstream newsroom, that is. Different experience, if you go to a place like APTN.

Erin: And do you think that both mainstream news and an outlet like APTN have a role to play in telling Indigenous stories and hiring Indigenous reporters?

McCue: It’s not an either or proposition. It’s absolutely vital that we have a strong Indigenous media voice. And I’m endlessly proud of the people that slug it out at Wawatay and APTN to bring our own stories to our own people. But that said, it’s also important that we have an Indigenous voice within mainstream news organizations as well. We can’t just play in our own sandbox because Aboriginal policy is, should be, an extremely important part of Canadian public life, so it’s important that that conversation goes on in the marketplace of ideas within Canada, and Indigenous journalists in the mainstream bring that voice. The fact of the matter is that not everybody in downtown Toronto, or Ottawa perhaps more importantly, is going to be tuning in to APTN or picking up Windspeaker, and so we need to have Indigenous voices in both fields.